If you’ll forgive my click-baity headline, I promise it really will be worth the time. See, I am horrible about not working on holidays. A few years ago, I came up with a technique to try and be a little bit better about it. From time to time I put together an email highlighting a detail from history I found worth remembering, and a few links to read further. I figured this Fourth of July, I’d share.

“It took me four days to find a bad job at low pay” -Newt Heisley, on finding work in advertising.

When I first read that quotation, I knew that the story of the POW/MIA flag had to be a little more exciting than what I’d always heard.

The version of the story I knew growing up, went something like this.

On January 7, 1970, LtCdr. Michael Hoff was launched from the USS Coral Sea as the pilot of a Sidewinder A7A Corsair aircraft. His mission was to perform armed reconnaissance over Laos.

I’m borrowing the in-line quoted portion from here.

You can read more about the aircraft here. (and an image credit.)

The weather in the area was clear and visibility was about 10 miles. Hoff’s aircraft was completing a strafing run near the city of Sepone when Commander Hoff radioed that he had a fire warning light and was going to have to bail out. The flight leader could not see the aircraft at that time. The leader did sight the aircraft just as it impacted in an area which was flat with dense vegetation and high trees.

Sepone

> The pilot of another aircraft reported sighting Hoff’s aircraft below him, when it was approximately 2,000 feet above the ground. The aircraft at that time commenced a roll and, prior to reaching an inverted position, a flash was observed which was initially thought to be the ejection seat leaving the aircraft. Immediately afterwards, the aircraft impacted and exploded. No parachute was seen, nor were emergency transmissions received.

>

>

> During ensuing search operations, aircraft reported that they received heavy enemy automatic weapons fire. Two aircraft were able to make repeated low passes in the crash area looking for a parachute or survivor, but the results were negative.

>

> As near as I’ve been able to find, it is here that the story of a woman known to readily Googleable history as Mrs. Michael Hoff, begins.

History has questioned Mrs. Hoff’s motives.

(To some she is said to have only noticed around 1971 when one of America’s oldest flagmaking shops, Annin Co published an article in the local press about having recently offered to design a flag for every country in the United Nations. To others, the very idea of the flag is at best an empty gesture of bureaucratic handwringing. I don’t find either of these positions particularly exciting, so I’m not going to mention them again — but I offer the dissenting critiques in the spirit of full disclosure.)

But I like to think that when she reached out to the Annin Co, Norman Rivkees was savvy enough to recognize what a good idea it was.

Military families have long shared in the military’s rich tradition of pageantry. (While it’s too much story for this post, if you’re interested you should check out the story of the Service flag designed by Robert L. Queissner, which pops up in some amazing places.) And Mrs. Hoff was right to note, there simply wasn’t a comparable expression for families who had sacrificed loved ones in service of the contemporary conflict.

According to Annin, Rivkees reached out to a New Jersey shop that as it just so happened had a connection to the service.

The official story from the Congressional Record is below.

Heisley joined the Army Air Force some time after graduating from Syracuse’s fine arts program. At the time of the design of this flag, Heisley was still working for an east coast agency, but sources suggest that by 1972 Heisley had built up enough of a reputation to move to Colorado Springs, Colorado and launch his own boutique shop.

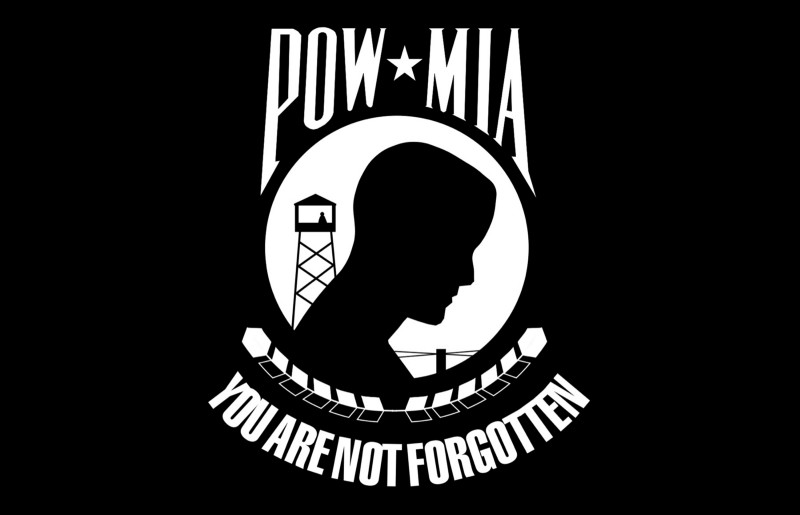

The design is simple, and the three elements have been interpreted by many more qualified critics than I. (And even Heisley’s own words on the story are worth a read.)

The guard tower, the barbed wire and the enfirmed soldier. Even the copy at the bottom of the illustration was drawn from Heisley’s own experience.

Which is precisely what I’m thinking about this Fourth of July. Because while we may think of this flag now in many different ways, it’s origins are one of the most American sort of stories I can think of. The way that Mrs. Hoff thought to contact a flag maker she had learned of reading a paper, that the project landed on the desk of a small advertising agency, that the work was powerful enough to give the designer the freedom he had earned at the end of a long career to start his own shop — that after serving half way across the world, it was that experience and perspective that let him build here, in the great state of Colorado.

That members of three of the most forgotten groups (military spouses, graphic designers, and flag makers) found a way to make use of the talents at their disposal and in doing so were able to accomplish this historically thankless task of acknowledging society’s most forgotten sacrifices is a reminder of our shared responsibility to do what we can with out voice where we are to make our communities more like the places we want to be.

Twitter

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Pinterest

Email