What I Think “Five Years’ Experience” Really Means And Why You Should Ignore It

Before I get too far ahead of myself here, I want to take a moment to say that if you’ve stumbled into this post because you’re encountering one of life’s most mysterious of frustrations you may find better answers on the resume game in Dr. John Sullivan’s delightful “Why You Can’t Get A Job … Recruiting Explained By The Numbers,” it’s one of the best explanations I’ve seen of how applicant tracking systems have changed the way we recruit talent.

But there’s one particular nuance that I’m not sure I’ve seen receive as much attention.

By some accounts, 2004’s introduction of “flyers” was the first iteration of Facebook advertising. I remember when I first started playing with the Facebook Ads platform, but that wouldn’t launch for years after the fact. In 2008 businesses started creating pages, and by 2012 the ad platform had matured enough to include conversion event targeting and user modeling.

Which is why it was so curious to start seeing job descriptions for “Facebook Marketers” as early that year (2008) that asked for 5 years of experience with the advertising platform.

The trouble is, it wouldn’t have been possible to have five years’ experience on the platform at that point.

The platform just hadn’t been around that long.

At the time, I wasn’t really in a position to do anything about it, so I kind of just forgot about it.

This afternoon, however, I was speaking with my sister who is just starting to explore the job market for the first time as an adult. It reminded me how baffling these sorts of requirements can be.

Yeh-Nah-Yeh Isn’t Wrong. There’s a few different school of thought as to what the phrase actually means.

- It’s an attempt to encourage applicants to self-select out.

- It’s an attempt to find an applicant with a measure of real world — not just academic experience.

- It’s an attempt to find someone familiar enough with a role to be able to hit the ground running.

- It’s the product of a hastily thrown together spec by a less-than-clear-headed hiring manager. This isn’t to say that these categories are the be all and end all. You don’t have to look too far however, to find several discussions where the topic is explored at length.

But, I think, really I’m of a similar mind on these as Raghav Haran (here.)

There’s 40 hours in the normal work week, and roughly 52 weeks a year. But people don’t really work 52 weeks, right?

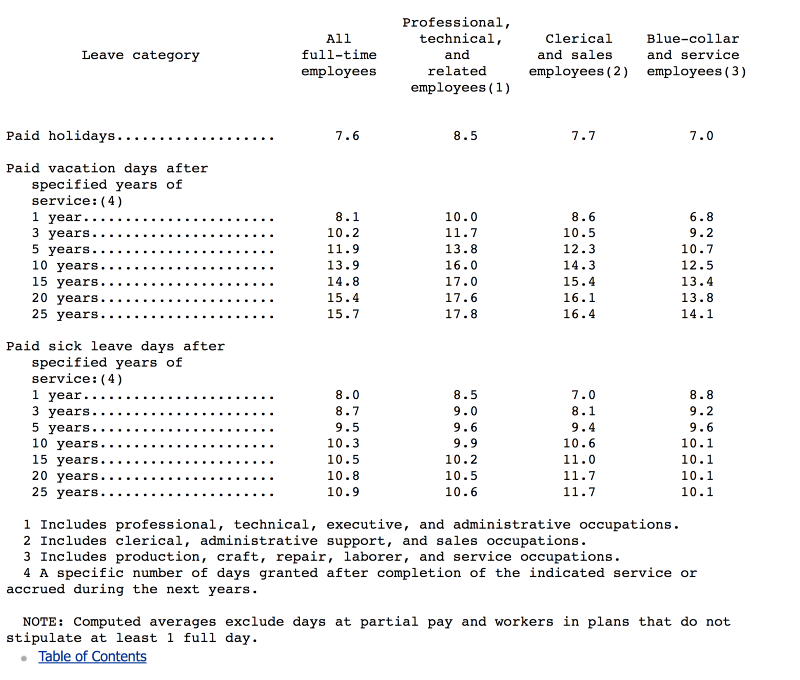

From The Fine Folks At BLS We could take the time to figure out the exact average number of days one might accrue over those five years, but for the sake of this exercise, let’s just assume that the average US employee gets 29 days off a year. 29⁄5=5.8 weeks off.

52 weeks in a year - 5.8 weeks off a year = 46.2 work weeks.

At 40 hours a week, that means one year of work is the equivalent of 1,848 hours of labor.

Now, for the sake of the exercise take that 1,848 hours and multiply it by the number of years’ experience (5) required. You’ll come up with 9,240 hours.

And then, if you’re anything like me, you’ll wonder about the impact my leniency with vacation days had on the number of hours.

In the time since the 10,000 hours metric was popularized, there’s been a growing bit of dissent.

Some, like Herbet Lui feel 10,000 hours just isn’t enough to become a master. Others, like David Kadavy, have highlighted just which variables you ought to be paying attention to.

Drake Baer notes what I think is one rather important bit of detail those who parrot the hourly figure often miss: the significance of the quality of the work.

It’s not as though you can just run out the clock and end up where you want to be. In fact, if you revisit the literature I think there’s one part worth considering.

“The distinction between work and training (deliberate practice) is generally recognized. Individuals given a new job are often given some period of apprenticeship or supervised activity during which they are supposed to acquire an acceptable level of reliable performance. Thereafter individuals are expected to give their best performance in work activities and hence individuals rely on previously well-entrenched methods rather than exploring alternative methods with unknown reliability. The costs of mistakes or failures to meet deadlines are generally great, which discourages learning and acquisition of new and possibly better methods during the time of work. For example, highly experienced users of computer software applications are found to use a small set of commands, thus avoiding the learning of a larger set of more efficient commands (see Ashworth, 1992, for a review). Although work activities offer some opportunities for learning, they are far from optimal. In contrast, deliberate practice would allow for repeated experiences in which the individual can attend to the critical aspects of the situation and incrementally improve her or his performance in response to knowledge of results, feedback, or both from a teacher. Let us briefly illustrate the differences between work and deliberate practice. During a 3-hr baseball game, a batter may get only 5–15 pitches (perhaps one or two relevant to a particular weakness), whereas during optimal practice of the same duration, a batter working with a dedicated pitcher has several hundred batting opportunities, where this weakness can be systematically explored (T. Williams, 1988).”

I don’t know that it’d be right to suggest that each hiring team put this level of thought into planning out their process, but I think in a way this makes a bit of sense.

For example, I know that I tend to try to have as many people working on production-quality work at one time as I can — but not everyone in my position manages their resources in the same way. What I might expect as standard performance from a Jr. Designer, for example, might better map up to another organization’s Associate Art Director role. If these two jobs have exactly the same title, someone somewhere is going to have to figure out how to unpack the experience and compare the candidates.

True too, is that the constraints of the environment don’t always allow for picking up the context necessary to really understand how any one given aptitude, experience, or talent fits into the bigger picture. Such perspective can really only be acquired with….well, perspective.

There’s something to be said about the value of being humbled by a lack of experience, but thus far I have found struggling to accurately catalog strengths and weaknesses (and then identifying the steps to leverage those strengths to mitigate said weakness) has proven far more rewarding.

Twitter

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Pinterest

Email